Foroba Yelen

In an off-grid rural African context, with international aid projects building lamps that light a space and not an activity, what form of light could support existing culture?

Understanding the unique social structure of rural Malian villages, we realised the importance of a light in this off-grid context. Young men work collectively in the fields and take responsibility of organizing all ceremonies within the village. Women run community gardens in parallel, generating commoncash for healthcare and general welfare of the village.

Both parties would tremendously benefit from a light, increasing productive hours. Keeping with the collective nature of this society, we designed community lights that are solar powered. These are maintained by appointed villagers and generates income for the village through a renting model.

Keeping with the collective nature of this society, we designed community lights that are solar powered. These are maintained by appointed villagers and generates income for the village through a renting model. Using local materials and available tools, we built two prototypes of our design.

These sturdy and mobile lights were welcomed by the village, and celebrated in a ceremony thrown in our honor.

Foroba Yelen ‘Collective Light’ was part of the 2011 London Design Festival exhibition. Collaboration with Peter Krige, Aran Dasan, Kevin Bickham.

Context

In an off-grid rural context, life can present distinct challenges. In the villages of Mali, where men and women work through the year, dusk brings an end to the workday, limiting their productivity.

The Need for Light

Men work the farms as a collective, and women run community gardens and produce craft objects, shea butter, commercial food items, and so on. Both would benefit greatly from a longer workday, especially in the fruit-picking season, where time is crucial.Even as international aid agencies pour in funding for street lights and public squares, they light a space and not an activity. Villagers would rather have light on their farms than have a lit pathway home.

Understanding Users

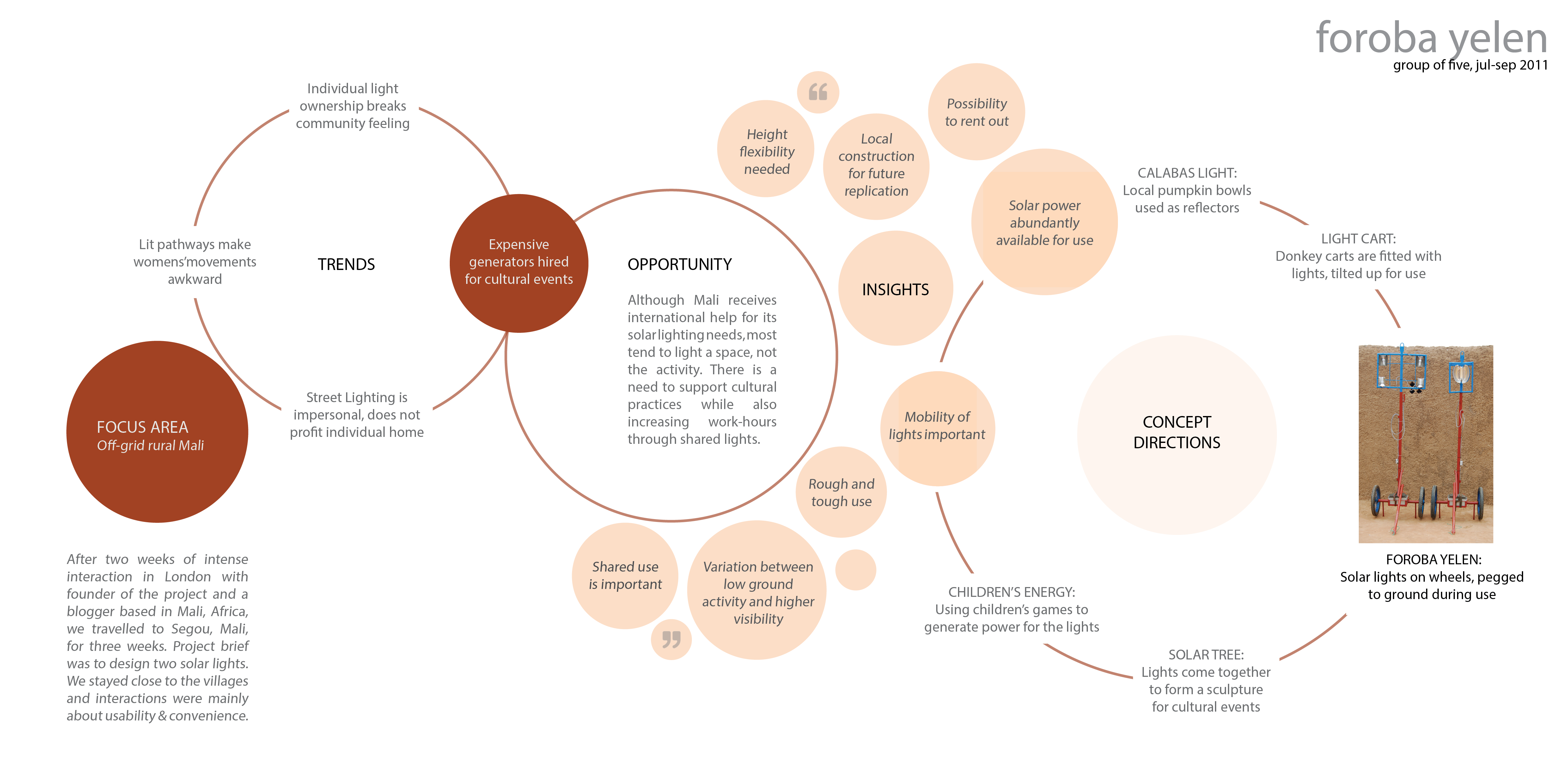

Using secondary and primary research approaches, we studied the unique context and environment of rural Mali. Activities included immersions, observations, day/night maps, and scenarios.Brainstorming Ideas

Various concept directions were generated, leveraging locals’ existing activities and products. We prepared these ideas for in-person co-creation sessions. Concepts included using Calabas, or pumpkin bowls, donkey carts, cell phones, and childrens’ stick-and-tires.

Co-Creation

Prepared concepts were shared with a select group of villagers for their prioritization and response. We learned that individually owned lights would break the collective grain of the social construct. Ideas were adapted based on the response and lights designed to be unitedly owned by the village and positioned at the Chieftan’s home.System Design

One full charge of the lights would last 10-12 hours. This meant that the lights could be rented out to neighboring villages for a fee. This way the lights would become an additional source of income for the village.Prototyping & Testing

The lights were designed to be simple and easy to replicate, hopefully inspiring a succession of products within the community. The lights were tested using prototype circuits and received curious looks from the villagers.Construction

The lights were built entirely out of materials easily available around us. Infant cereal containers, motor wheels, and zip ties feature prominently. A solar-cell charger was built from scratch and installed permanently on the chieftan’s home.

Celebration

The lights were inagurated with a dance party where the village came together. They were transported by a donkey cart and turned on by the village chief. The lights overshadowed the generator-lit lamp typically hired for the dance. (seen on the left edge of adjacent photo)

Foroba Yelen ‘Collective Light’ was part of the 2011 London Design Festival exhibition. Collaboration with Peter Krige, Aran Dasan, Kevin Bickham.